Originally posted in Counter Arts on Medium on September 3, 2024

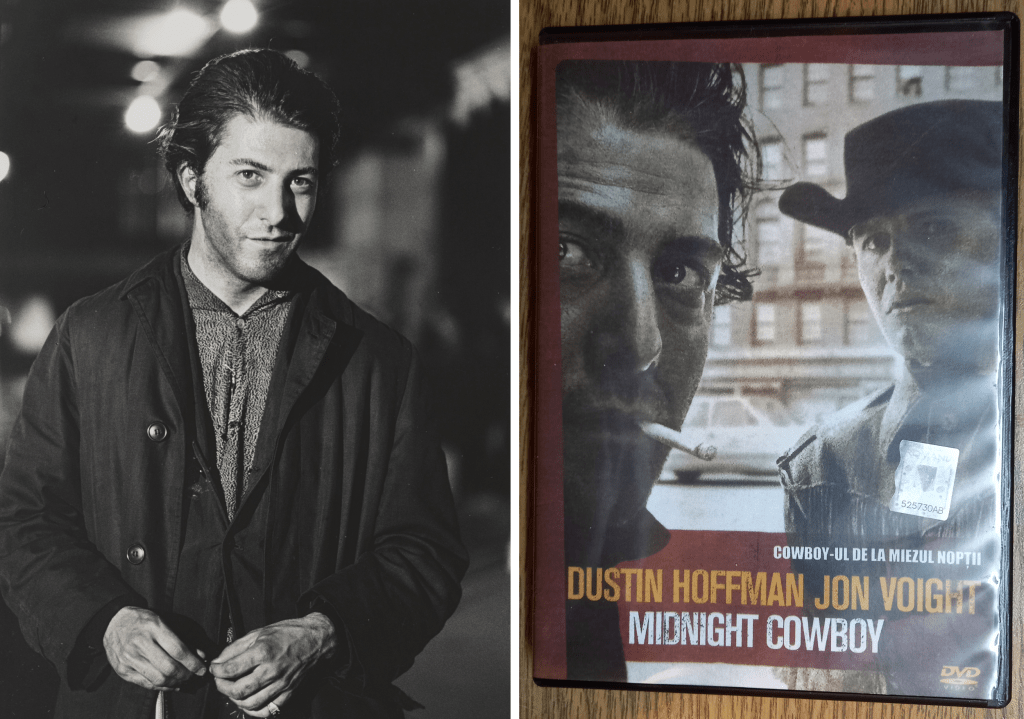

I watched Midnight Cowboy with a friend the other day, and seeing it on DVD for the second time, it struck me how strong it was and how visually exciting after all these years. It lays out a compelling story with stellar acting, is both very complex and fresh image-wise, and holds up well on a second, third, and even fourth viewing. (I’ve done the latter two with a voiceover by Jerome Hellman, the film’s producer.)

Midnight Cowboy (1969), while not as well-known as The Graduate (1967), is probably the film where Dustin Hoffman gives his career-best performance. It’s a film far more intricate and artsy than The Graduate — even as I appreciate the qualities of this Summer of Love film too. But Midnight Cowboy, with its outstanding script and performances, is a lesson in dramatic emotional tone, the way few films are — I’m thinking now of Chicago (2002).

The two films have very little in common, Chicago being very glib and razzle-dazzle whereas Midnight Cowboy is smoky — literally, too, as Dustin Hoffman’s character smokes a lot, despite having a pulmonary infection — , grimy, and burned with color, let’s say, but there’s a range of feeling that opens up quite widely in both, even as that’s not very apparent in Chicago.

Okay, back to the film under discussion. The opening sequence, one that’s rather long as it needed to accommodate the credits, starts with Joe Buck (Jon Voight) walking in cowboy boots and then traveling on a bus from Texas to NYC. The camera lingers on several characters on the bus, some of them people playing themselves, heeding one direction only (for instance, to look sad). Joe tries to engage with some of them, including with a woman who travels with her daughter, who reads a Wonder Woman magazine — one meaningful detail among many others in this film.

Soon after arriving in the big city, Joe meets Ratso (Dustin Hoffman), and, even though he doesn’t know it yet, Joe has met a partner in (small) crime.

At first, Ratso — Rico, in fact, from Enrico — doesn’t care about Joe and sends him on a wild goose chase only to get $20. But then he’s there for Joe when he’s out of hotel money, offering him a place to stay in his squalid disaffected tenement room and teaching him his tricks on how to scrounge a few bucks, all while trying to offer him solutions on how to score in his hustling racket, for which Joe is so woefully unprepared.

Although based on a novel by James Leo Herlihy, the script opened up to include many other telling scenes to create well-rounded characters out of the two protagonists. Some of them were inspired by actual events witnessed by director John Schlesinger and writer Waldo Salt, from a man down on the sidewalk whom no one rushes to help, to a mother and child, both on some kind of drugs, playing with a rubber mouse in a diner. Other sequences were based on improv sessions — between Hoffman and Voight and among actors from Andy Warhol’s Factory.

Warhol’s coterie included, in the film, the famous Viva and Ultra Violet alongside many other less familiar faces doing drugs and having sex at a party while also acting for the camera, the way it happened in NYC in several places at the time. According to Hellman, some would-be artists were filming people at parties as part of their projects — probably cottoning onto what Warhol was doing at The Factory with his films, only, of course, Warhol’s films were terminally long and very boring, much as they also broke new ground.

According to Hellman, the man on the sidewalk scene came out of something Hellman and British director John Schlesinger, along with others of the film’s crew, saw on a New York street. Hellman said it may have been on E 42nd St. but was not sure. They filmed it on 5th Avenue, next to Tiffany’s. Someone fell down on cue and people passed him by as if he wasn’t there. What was hopeful in Hellman’s commentary was that when they shot the scene people stopped to try to help — repeatedly. But then, as it’s also bound to happen, on one occasion they didn’t, and they were able to have their scene as they wanted it.

Hellman commented that Ratso, with all his schemes and tricks, is actually at his core a rather common middle-class man. When Gretel (Viva) steps into a restaurant with her twin brother, takes a photo of Joe, and invites them to their party, Ratso is dismissive of them, calling them weird. Hellman is, of course, right: Ratso is about cheap tricks, not about grand gestures, much as he dreams of the latter.

He dreams of moving to Florida and being the chief of the roost there, running by the ocean with Joe — when in fact he has a lame leg — , enjoying the camaraderie of plenty of women as their central male figure, walking about elegantly dressed, when in reality he has to wile and guile an Italian-American woman with his Italian at a laundromat to be able to load one of their shirts — Joe’s — with the woman’s laundry.

Speaking of Joe’s shirt, the costumes — by Ann Roth — are quite nice in this movie, starting with Joe’s cowboy boots and cowboy shirts, moving on to Ratso’s purple suit and then to a fur coat worn by one Shirley (Brenda Vacarro in her first movie role), who finally has sex with Ratso and pays him, making him believe that he could be a hustler, after all.

The scene with Brenda Vacarro is partially inspired by real life too. According to Hellman, Schlesinger was friends with a wealthy New Yorker who liked to humiliate the men she slept with by overpowering them with her smarts. How? By making them play Scrabble. A game of Scrabble then became part of the film, with Joe making up the word mony for money, since these were the letters he had seen from his hotel window when he arrived in New York: MONY from the neon initials of Mutual Of New York.

But then Ratso gets sick and wants to go to Florida while he still can, and Joe is scrambling to make a lot of money for the bus fare and other travel expenses. He’s experiencing deep empathy for his friend, even as he’s unaware of how dire the latter’s situation is, and he’s determined to make the money for their trip.

So Joe, who has shown himself to be a softie, becomes violent. He meets a closeted, masochistic gay man and when the latter doesn’t produce enough money, he punches him in the face, drawing blood.

Then they leave for Miami. Ratso is sick, very sick. He’s sweating and he’s cold, and he fades in an out of consciousness, though he still has a mind to tell Joe that he hopes he didn’t kill that man.

And then he dies.

Joe had just bought new colorful clothes for both of them, while also stuffing his cowboy boots, shirt, and coat in a garbage can on the street. He was so decided to begin his new journey then and there that he didn’t even wait to get to Miami and sell them. Or maybe he now thought they weren’t worth much, since they didn’t bring him much money in New York.

This is where the film ends. When they first filmed the closing scene, with Ratso dead on the bus, his head against the window, it had just started to rain. The cameraman — on a support mounted on the side of the bus — stopped filming. It was a shame, producer Hellman said in 2004, because those raindrops could have been there symbolically, like teardrops.

But teardrops would have changed the tenor of the film. It was never sappy, never bleeding sympathy for Ratso. On the contrary, it tried to mix Joe’s naïveté with Rico’s brand of restrained grit in a way that made their camaraderie so very touching to watch. Joe, a kid at heart, asking Rico where he put his boots (Rico had pulled them off when Joe had fallen asleep). Rico, pretending to be tough about it. Rico, telling Joe he needs to wash more if he wants to be a hustler. Joe, responding like a boy in a boy fight, trying to attack Rico, going from the topic of who was filthier to whether Rico has ever had a woman. To which Rico ripostes that Joe’s cowboy shtick doesn’t impress any New York woman, if that’s who he’s after.

The above conversation, in a tenement room, where the pair had no electricity but somehow enjoyed running water, came about not only from Waldo Salt’s script (based on James Leo Herlihy’s novel) but also, as I’ve mentioned, from improvisational interactions between Hoffman and Voight. Hellman was delighted about how the two inhabited their characters and he was equally pleased with how Salt managed to condense hours of improvisation into a few impactful minutes in each scene.

Hellman mentioned, in particular, a bit where Joe and Rico shudder in their beds in the cold. Joe had sold his radio at this point (it was his one prized possession besides his cowboy clothes and boots) and they only had each other for company. And in that scene, Rico pulls at the newspaper wrapped around them between layers of clothing and he tears a scrap he then tries to read. This, Hellman said, was Hoffman’s idea, and it made, indeed, for a few memorable seconds in the movie.

Speaking of minutes and seconds, the pacing in the film is just great. The viewer has time to visually embrace the two protagonists in their tenement room but then is also offered an extravaganza of flashing frames, almost in a strobe-like fashion, including flashbacks from Joe’s life and glimpses of the psychedelic party.

A Tragic Love Story and Women’s Power Over Joe

There’s a lot in the film about Joe’s background. The flashbacks tell a story where he was raised by his grandmother, a woman who liked his men and also her neck massages from a young Joe, and then they insist on images of him and Annie, seemingly his first and only love. It didn’t end well, as Joe and Annie were both raped by a gang of young people and Annie became “crazy Annie” and was institutionalized.

Despite this story, however dramatic and potentially traumatic for Joe too, the film manages to emphasize the power women have over the young Texan, rather than the tragic denouement of his relationship with Annie. Joe is mesmerized by women, starting with his grandma and Annie, and as he travels by bus from Texas to New York he smiles and talks to some of them, whether they are younger or older. He also listens on the radio to an interview with sexually liberated women and he’s pretty excited, thinking he will score with so many of them once he arrives in NYC in his attractive cowboy — “stud,” since he admits he’s not much of a cowboy — clothes.

In fact, Joe knows very little about New York women, about women in general, and even about himself. He thinks he’s only good at one thing: making love, having sex, so at one point he concluded that he could make money at it, left his dishwashing job, and boarded a bus to New York.

Hustling New York women, however, are several bars above him in this racket. When he meets Cass on the street, she drags him into a hotel room and undresses him while talking to her rich lover, the whole operation making the viewer feel that Cass is unwrapping a gift. The snaps on Joe’s shirt pop one after another and Cass’s older lover on the phone is none the wiser, much as he does suspect something when Cass talks to Joe. Cass says she was talking to her dog. Older lover, young lover, dog, Cass plays with them all. In the end, it is Joe who gives her cab money, when she puts on some theatrics about having none, rather than Joe getting his suspected hustler’s fee.

In the end, after various encounters, he only beds one woman who pays him. But then it’s too late for Ratso and they have to leave for Florida.

The power differential remains, however. Shirley, who pays him, is the one who belittles him for not being able to spell money and for coming up with such pitiful words for Scrabble as man. Bitter victory, indeed.

It’s all for the better, of course. When they arrive in Florida, he’s a changed man, realizing that he could find some job outdoors to please him much more than trying to score with women for money. And as Hellman notes, when he meets a nice young woman in a restaurant where he gets breakfast for him and Ratso, he’s finally able to look at her unencumbered by his former desires of playing — nay, being — a stud for money.

Hellman’s (Problematic) Comments on the Women’s Lib Portrayed in the Film

In 2004, commenting on Midnight Cowboy, Hellman was more than a bit nostalgic for the days of 1968, when the film was shot, repeatedly referring to the fact that you could find anything on 42nd Street, from drugs to prostitutes and, I guess, men collapsed on the sidewalk no one pays attention to.

According to him, when they filmed the party sequence everybody got stoned and people also started having sex everywhere, including on the floor of the studio and of the actors’ dressing rooms. Hellman was, apparently, the only one sober those days, since as the film’s producer he had to take care of everybody else.

He talked fondly about those three or four days of filming with Andy Warhol’s people. Schlesinger knew Andy Warhol and appreciated him, so he came up with this idea of the party sequence, even though, Hellman says, Schlesinger was probably not used to drugs himself. But for the party they remodeled part of the studio to look like a loft and kept people there for days on end, giving them food and grass, and trusting them to provide some good acting, even though they weren’t professionals.

Schlesinger tried some of the grass too, and, according to Hellman, he suddenly became aware of several things he wanted to do in his film, for instance showing the importance of touch in that party sequence and others, including the scene with the rubber mouse. Part of it, too, had to do with him having been a closeted homosexual, who had only come out before the film was shot.

Indeed, Hellman’s comments are priceless about many aspects of making the movie that one may miss when seeing it for the first, second, third, or even fourth time. Joe and Rico, for instance, do not touch in the movie, except when they walk up a staircase going to the party and Rico is sweating and not well. Joe uses the edges of his shirt to make him presentable. According to Hellman, Schlesinger was very careful with these undertones, even though given Joe and Rico’s rapport and kidding around — which, again, now seems more restrained than it would have been for those two characters — it would have been natural for them to hug and slap each other on the back now and then.

That said, Hellman applauds with no reservations the liberated times, even though, despite the way it was portrayed in the film, more individual freedoms for women, including sexual, didn’t, in fact, mean that women had found equality with men. Women’s jobs and paychecks were still pretty much what they had been, only now, from objects to look at and occasionally engage with, and domestic help to keep your house clean and raise your kids, women had also become easier playthings.

Could it be that Schlesinger, being a gay man, portrayed women as having more power than they actually had? It’s enough to look at how women use their wiles in Midnight Cowboy — in bed, in sex — to realize that maybe this was one dimension where women intimidated Schlesinger, so he inflated this kind of rapport between men and women, when in fact, in 1968 women were still paid much less and appreciated much less for anything other than their looks and sexual availability.

And as for sexual liberation, as (British) social historian Virginia Nicholson documents in How Was It for You? Women, Sex, Love, and Power in the 1960s, before the Pill came along, many girls found themselves one second, sexually liberated, and the following second, pregnant. Okay, so the Pill did help women engage in sex more freely, but as Nicholson points out, between a roll in bed and one of a doobie, they still had to scrub toilets and put cooked meals on the table.

If anything changed, Nicholson writes, quoting artist Nicola Lane, it’s that women had to be what they had been and more, because they now had to look sexy too and were often coerced to take drugs, whether they wanted or not, because it was the thing to do. The other thing to do, Lane says, was to be quiet. Not, by any means, a thinker. Quiet and willing to please men sexually, because it was en vogue — pressured into doing it and accepting partners sleeping around even as they may have wanted a monogamous relationship for themselves.

How is that women’s liberation? But yes, all the play for free that heterosexual men engaged in must have seemed like liberation to Hellman — liberation for those men, if they were inclined to play the field and still have a woman at home waiting on them.

An Unlikely Couple

Hellman says in his 2004 commentary that they knew they wanted Dustin Hoffman for the part of Ratso — they had hoped to work with him even before he became famous with The Graduate (1967) — but tested various actors for the role of Joe. Dustin Hoffman, too, was asked to chose between the two final contenders, and he did, saying that when he looked at him and the first man in a scene, he looked mostly at himself, whereas when he had Jon Voight in a scene with him, he looked at Jon Voight. So it was decided: Jon Voight would take the part of Joe.

The casting, according to Hellman, involved having Voight improvise with Hoffman, then be interviewed by a New York reporter (played by Waldo Salt), and, finally, stride through the New York crowd.

Roger Ebert commented at the time that the relationship between Ratso and Joe should have been about them helping each other grow rather than about two men essentially stuck together because life pushed them into a corner. But Ratso and Joe do experience personal growth together and leave their marks on each other, even as Joe is not very aware of it, as he has little self-awareness in general. Joe comes to care for Ratso and while he doesn’t learn from him his soft tricks — getting, instead, to a point where he clobbers an old closeted gay man for money — , he does connect to Ratso’s kindness.

Despite his bravado — there’s a famous scene in the movie where he crosses in front of a yellow cab, vociferating at the driver to be more mindful of pedestrians — , Ratso is a rather tender petty criminal. He refrains from hurting pedestrians and store owners much, pilfering instead small food items and doing the occasional shoe-shine routine, one that his father did for a lifetime. In their tenement room, Ratso is the one making their meals, cooking them with love and care.

But Joe insists Ratso should be his manager, so Ratso does a bit of pickpocketing to steal some contact info and help Joe find a woman to sleep with for money, and he goes with him to that psychedelic party even though he can barely stand and walk at this point. At the same time, he also tries to make Joe understand that his cowboy act doesn’t really hold.

As an aside, John Robert Lloyd, the production designer, obtained permission to pluck out the interior of Ratso’s room in the film from a tenement building they’d started shooting some scenes with, and recreated it on the premises of their studio, Filmway Studios in Harlem. Hellman said the guy surprised all of them with the veracity of the recreated environment — with the look of what they got to call the X flat.

Is Ratso molded in any way by Joe? Hard to say. Ratso is all in all a far more rounded person than Joe. But he probably becomes a little more lighthearted with Joe around. Joe, who was laughing about Ratso peeing himself on the bus, not realizing that the poor man was so very near his death.

The film touches quite a few chords but doesn’t hit them, despite Ebert’s assessment, as it stays away from melodrama. It’s only when Ratso realizes he’s close to not being able to walk anymore and then close to dying that he allows himself self-pity, but even then the moment is not milked for melodramatic effect but presented more curtly, dramatically but not histrionically.

As someone commented on Ebert’s review, Ratso is the epitome of a survivor who is courageous enough to make up his own rules and petty schemes and abide by them. But Ratso is more than that. His rules are not confined to allowing himself room to cheat and swindle. He’s also a man with a big heart and a spiritual man, both sides coming to the surface clearly when he takes Joe as his protégé of sorts. He wants to help another man and he wants to leave a legacy.

Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight were both nominated for Best Actor in a Leading Role, but that Academy Award went to John Wayne for True Grit.

A Sixties Film

For all the grime in Joe and Rico’s life, the film is rich in color. Mostly, though, it’s just bright spots of color in an otherwise grayish environment, and the costumes add to that aesthetics. Joe’s shirts are bold green, blue, red, and purple, and they do make an impact. Then there’s the red of tomatoes Ratso pilfers in the street, the orange of Florida oranges in two posters by the window and in three more on two of the walls in their drab and squalid tenement room — there’s also an audio commercial for Florida orange juice — , a blinking plastic Christ with a red robe, the red tint of Joe and Shirley in a darkroom, Shirley’s yellow-orange sheets, and so many other color touches like this, including the purplish red tint of Ratso’s tenement building and his purple suit.

Then there are various neon signs pulsating through the story and getting stronger at night, including the vivid environment of an arcade and the colorful lights along with lit windows on 42nd St., at the time a place where sex workers and drug dealers mingled among dilapidated, run-down buildings.

Importantly, there’s also the letter X shot various times — spray-painted on Ratso and Joe’s tenement building door and, for more than good measure, taped to all the panels of their two double windows. It’s an X of paths closing, an X of nothing is going to come of this — and yet, in many ways, it does, for both the central characters.

It’s worth noting that parts of the film, which include Joe’s story with Annie, is in black and white, which signals the quality of these sequences as flashbacks but also serves to emphasize the vibrancy of the present against that backdrop. While Joe is affected in some ways by what happened between him and Annie and has nightmares about it, he’s nevertheless looking at New York like a child at a candy shop window. He hasn’t lost his childlike innocence, which is, perhaps, why Ratso, a kindhearted man, takes to him the way he does.

There’s also MONY in Mutual Of New York, always out of reach on the wall of a building seen through the hotel window, yet always alluring.

There are fashionable women, with hairspray in their rigid hairdos and lots of false eyelashes (Virginia Nicholson says Twiggy used to wear three sets of those). Women who stride to and fro in New York as if they owned the place yet, with few exceptions, depend on someone else to live in the City and, ultimately, to look sexy.

Midnight Cowboy is also a film where the camera is very mobile, panning and zooming and changing viewpoints and lenses constantly. In one scene Rico is looking at Joe trying to make it into a hotel and meet a woman as her escort, and then Rico is dreaming, very vividly, about Florida, a place of spectacular skies and blue ocean waters and with rich women enjoying their leisure. One segment or another is about cramming action in a tight staircase space and then the room of the party opens so wide, everything happens here, there, everywhere, all seemingly in the same larger frame. Women are flashing their breasts to us, others are topless with their backs to us, and consciousness and celluloid are dissolving, psychedelic-style, in a way suggestive of cells knocking against each other, merging, and floating away from each other.

The Music

The film’s opening and closing sequences are memorably connected to a song performed by Harry Nilsson a.k.a. the Fifth Beatle. The song is titled “Everybody’s Talkin’” and it ties into the idea that Joe is going through life listening to all these women, to his radio, to Ratso, and yet he doesn’t actually listen. As music illustration, it’s a perfect fit, and not just for the lyrics — Nilsson had one of the most melodious male voices of the sixties, and it works its magic in the movie: it makes you expect something optimistically in the beginning, just as Joe Buck does, and at the end of the movie, when Joe is shaken by the death of his friend, it makes you mourn the charms of Ratso and the demise of a hefty part of Joe’s innocence.

Three Academy Awards

Midnight Cowboy earned three Oscars in 1970: for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay.

Enjoy!

*

Thank you for reading! As always, pins and shares are much appreciated!

Tp a happier, healthier life,

Mira